Paul Klee and the Childhood Embroidered in Colors No One Remembers

There are memories that do not live in words or photographs. They shimmer in hues unnamed, echo in lines that spiral inward, surface in silent rhythms on paper. In Paul Klee’s work, childhood is not revisited—it is reimagined. Not as a narrative, but as a color that once existed in the soul’s language before language itself.

To look at Klee is to enter a map without roads, a diary without dates. His childhood appears in fragmented lullabies of pigment, stitched like forgotten embroidery into the edge of waking. It is not about remembering—it is about feeling again, without needing to name. And in this, Klee reveals the most sacred truth: the earliest self is never lost, only painted in tones that we no longer know how to pronounce.

Table of Contents

- The Alphabet of Lost Light

- Grids that Breathe in Whisper

- Red That Remembers a Lullaby

- The Playroom of Abstract Time

- Geometry with the Scent of Chalk

- The Puppet as Prophet

- Lines that Tremble Like Sleep

- Cradles of Shifting Shadow

- Paper Textures of the Subconscious

- The House Drawn from Inside Out

- Warm Grey and the Taste of Solitude

- The Scribble That Speaks to the Sky

- Toys Hidden in the Square

- Music That Folds into Color

- The Hand That Writes in Silence

- When Childhood Becomes Glyph

- Patterns From the Dream Before

- Faces as Fragments of the First Gaze

- Earth Tones and the Breath of Memory

- The Echo in the Empty Page

The Alphabet of Lost Light

Klee’s early abstractions feel like language trying to be born. Lines and shapes gather not to form syntax, but to suggest it—as if memory speaks in an alphabet that only children and the very old can read. Light is not used to describe; it is used to whisper.

Grids that Breathe in Whisper

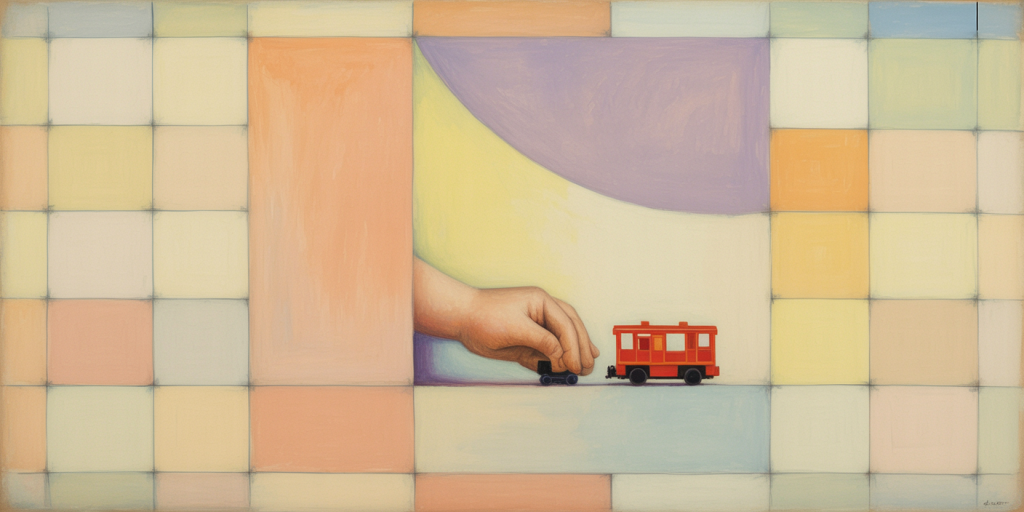

His many grid-based compositions pulse with life, never rigid. They are playgrounds disguised as order. Each square pulses with slightly different emotion, like tiny windows into the cells of nostalgia. The whisper of childhood breathes between the lines.

Red That Remembers a Lullaby

Red in Klee’s palette does not scream. It hums. It wraps around forms like a lullaby sung in the back of the throat. His reds are never uniform—they bleed, they glow, they rest. Red is a mother’s voice hidden in abstraction.

The Playroom of Abstract Time

There is no time in Klee’s childhood—only rhythm. A moment becomes a century; a second becomes infinite. His canvases suspend time in layers of motionless dance. Shapes float like toys half-remembered, always on the verge of fading or flying.

Geometry with the Scent of Chalk

Klee’s lines often echo schoolroom blackboards—but altered, softened by memory. They carry the scent of chalk dust and the echo of children’s fingers tracing circles in the air. His shapes are not rules; they are recollections of structure, playfully betrayed.

The Puppet as Prophet

In his figural works, the puppet recurs not as a toy, but as oracle. Expressionless, jointed, angular—it becomes a surrogate for the child-self, voiceless but full of wisdom. The puppet in Klee’s hands is the soul without disguise.

Lines that Tremble Like Sleep

No line in Klee is truly straight. They breathe, shift, tremble like the hand of someone drawing just before sleep. These are dream-lines, subconscious trails. They trace the inner corridors of emotion, leading nowhere, and everywhere.

Cradles of Shifting Shadow

Shadow in Klee does not threaten. It cradles. His muted tones wrap forms like evening light on a child’s face. These shadows shift as memory shifts—subtle, incomplete, generous. In his world, darkness does not conceal; it comforts.

Paper Textures of the Subconscious

His surfaces feel intimate, like old notebooks or the back of school worksheets. The paper texture matters: it invites touch. The very grain of the material becomes part of the memory. What is painted is not image, but residue.

The House Drawn from Inside Out

Houses in Klee’s work are not shelters—they are metaphors for the self. Windows float, roofs bend, walls breathe. The child’s perception of space is honored: inner feelings become outer form. The house becomes a memory with stairs.

Warm Grey and the Taste of Solitude

Grey in Klee’s palette is never absence. It is warmth wrapped in quiet. It tastes like rainy mornings spent alone in thought. Grey is the pause in the song. The soft texture of remembering without resolution.

The Scribble That Speaks to the Sky

Scribbles in his drawings act like prayers. They rise, unravel, seek. They do not form pictures, but they form meaning. A child’s drawing made with closed eyes—this is Klee’s faith language. Pure, primal, and vertical.

Toys Hidden in the Square

Within many geometric compositions, small shapes hint at toys. Wheels, blocks, strings of beads. They are not drawn fully—only suggested. The viewer must search as a child does, with wonder and patience.

Music That Folds into Color

Klee, a trained violinist, painted like a composer. Color and line move like melody and harmony. Repetition, variation, silence—all play across his surface. Each work feels like a memory set to music too old to be sung.

The Hand That Writes in Silence

Klee’s hand is ever-present. Every line feels handwritten, not mechanically drawn. It is a personal letter from past to present. A silent monologue to the self, stitched in pigment.

When Childhood Becomes Glyph

Many works resemble invented alphabets, runes, signs. Klee turns the language of childhood into visual glyphs. These symbols do not instruct; they evoke. They are not to be deciphered, but held.

Patterns From the Dream Before

Before memory, before language, there is a dream. Klee paints its fragments. Circles, triangles, dashes—they drift across his surface like elements from a forgotten cosmology. He names what cannot be named, patterns the shapeless.

Faces as Fragments of the First Gaze

When faces appear, they are not portraits but echoes. A curved mouth, a pair of hesitant eyes. They do not speak. They gaze back from the haze of a crib, from the blur of infancy. They are the viewer before the mirror existed.

Earth Tones and the Breath of Memory

Klee’s use of ochre, sienna, muted rusts and clays roots his work in earth and history. These are not bright nursery colors. These are tones that breathe from the soil of feeling—rich, loamy, tender.

The Echo in the Empty Page

Even his negative space speaks. The empty areas do not lack; they wait. They are the pause in memory, the breath between recollections. Klee lets silence be part of the music. He paints the unsaid.

FAQ

Who was Paul Klee?

Paul Klee (1879–1940) was a Swiss-German painter known for his poetic, symbolic, and experimental approach. He was a teacher at the Bauhaus and a pioneer of modern abstraction.

Why is childhood so important in Klee’s work?

Klee saw childhood as a source of purity, instinct, and creativity. He sought to preserve its intuitive language through abstract symbols, colors, and dreamlike compositions.

What techniques did Klee use?

Klee used watercolor, oil, ink, and mixed media. He often worked on paper, applying color in translucent layers and using fine lines to create rhythmic, musical structures.

Is Klee’s work surrealist or abstract?

Klee defies strict categories. Though often abstract, his work carries surreal, symbolic, and expressive qualities. He called his art “taking a line for a walk.”

What inspired Klee’s palette?

Klee’s colors were influenced by nature, memory, and music. His travels to Tunisia deeply impacted his use of luminous and earthy tones.

Final Reflections: Memory Stitched in Invisible Thread

Paul Klee did not paint what he remembered. He painted how it felt to forget and then remember again, faintly, like a scent in the wind. His childhood was not reproduced, but re-felt—not as scene, but as vibration.

In his delicate lines, his bleeding colors, his trembling shapes, we find our own lost moments. The invisible corners of first perception. The hush before identity. His work invites us to look with eyes that remember before we knew we were looking.

Klee embroidered childhood not in narrative, but in tone. Not in clarity, but in warmth. And perhaps that is the only way to return to what matters most: not by walking backward, but by listening to the threads of color no one else recalls, and letting them lead us gently home.