The Fruits of Goya and the Rot of Hope

- Francisco Goya

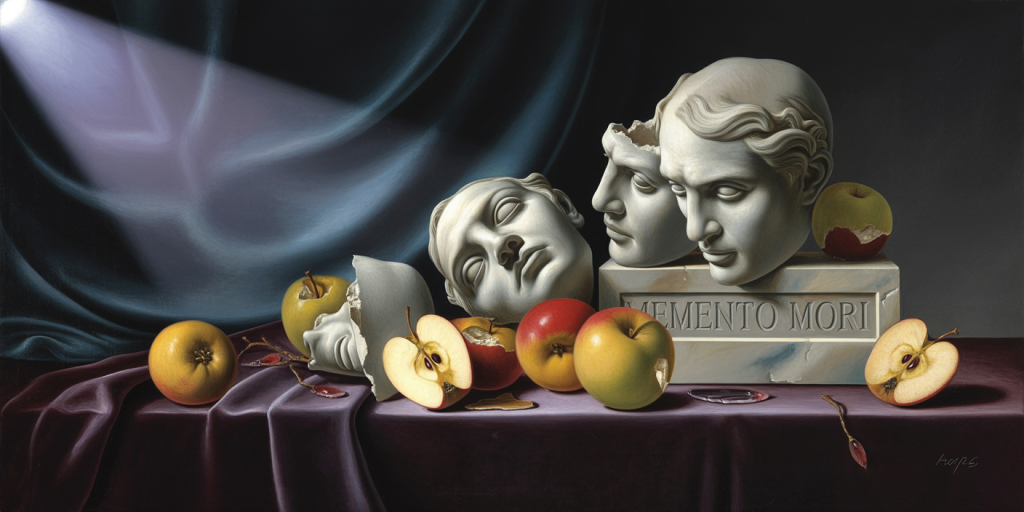

When light retreats behind the hills of the soul, and the orchard of the mind yields not nourishment but decay, one enters the disquieting world of Francisco Goya. Here, fruits do not glisten with promise—they sag with dread, split by invisible worms of despair. The air is heavy with silence. Hope, half-bitten and forgotten, withers on a darkened branch. In Goya’s orchard, no child runs, no basket gathers sweetness. There is only rot, and the solemn reverie of those who remember what ripeness once meant.

This is not the fruit of Eden, but of exile. Not of abundance, but aftermath. These forms—apples, pomegranates, figs—stand as witnesses to a deeper erosion. Their contours, painted with deliberate gravity, whisper of sickness in the world and sickness in the self. Goya does not illustrate fruit; he exhumes it. And in doing so, he exposes the fragile skin of human longing.

Table of Contents

- The Orchard of Lament

- Hues of Spoiled Flesh

- Shadows Where Flies Gather

- The Knife in the Composition

- When Fruit Becomes Mourning

- Skins That Remember the Sun

- Bitten Symbols of Silence

- The Decay Beneath the Frame

- Rot as Metaphor for the Soul

- Goya’s Palette of Illness

- Wormholes Through Innocence

- Still Life as Silent Scream

- The Gravity of Texture

- Time’s Fingerprints on Flesh

- Between Baroque and Blackness

- Death in the Light of Day

- Fragments of Forgotten Feasts

- Quiet Violence in Brushstrokes

- A Psychologist with a Palette

- Aftertaste: Rotting Memory and Lingering Color

The Orchard of Lament

In Goya’s painted fruits, the orchard becomes a graveyard. Each apple seems plucked not from a tree but from an abyss. The arrangement defies bounty—it drapes itself in sorrow. The traditional cornucopia spills not with festivity but with funereal meditation. One does not taste these fruits; one mourns them.

The composition often pulls us in with deceptive familiarity. A still life? Yes. But not still. The decay is active. The fruit collapses inward, tender with ruin. This is the stillness of rot, not of peace.

Hues of Spoiled Flesh

The palette is subdued but feral. Reds like dried blood, browns like old bruises, yellows turned to ochre by the rot of days. There’s an internal temperature to Goya’s fruits—neither warm nor cold, but festering.

The edges bleed softly into shadows. There’s no sharp boundary between skin and silence. One might say these fruits suffer. And color, here, is no longer decoration—it is diagnosis.

Shadows Where Flies Gather

What’s left unsaid in Goya’s works is often louder than what is painted. We can almost hear the buzzing of unseen flies, their chaotic orbit hinted at by empty spaces and glistening dents on soft, collapsing surfaces.

Shadows congregate not just beneath the objects but inside them. These are not passive fruits; they have cavities, wounds, voids that throb with implication. The shadow is not absence—it is presence in mourning.

The Knife in the Composition

Sometimes, a blade rests beside the fruits. Innocuous? Never. It is the suggestion of violence past. The apple half-sliced, the fig torn, the citrus bled dry—this is not preparation for a meal but an autopsy of the soul.

Goya composes his arrangements as one composes an elegy. Every object mourns. Even the knife, gleaming or rusted, is a eulogist.

When Fruit Becomes Mourning

To behold Goya’s fruits is to enter a chapel of desiccated hopes. They are painted as if he once loved them—and watched them betray that love by turning sour. The table becomes a confessional. We do not eat here; we confess what we once desired and failed to preserve.

There is no abundance, only memory. Each fruit is a ghost of what it could have fed.

Skins That Remember the Sun

The fruit skin, often blotched and wrinkled, retains the faintest sheen—remnants of a sun that once caressed it. This residue of warmth aches more than absence. It is a lie of vitality, clinging to surfaces where life has fled.

Goya doesn’t forget the sun. He paints its aftermath. Skins are not shields here; they are bruised histories.

Bitten Symbols of Silence

A bite taken, a pulp exposed—these elements speak in silence. Who bit them? Why? Goya leaves it unanswered, letting the viewer become both witness and suspect.

There is something deeply carnal and equally metaphysical in these gestures. A communion desecrated. A hunger unfulfilled.

The Decay Beneath the Frame

We imagine what lies just beyond the painted edge. More rot? A hand? A carcass of desire? Goya teases the viewer into hallucinating continuation. The canvas breathes with death that spills beyond its constraints.

The unpainted is never empty. It presses in. One suspects that decay is watching us back.

Rot as Metaphor for the Soul

Goya’s fruits decay not because he delights in ruin, but because he recognizes it as inevitable. Their decomposition mirrors the withering of belief, of love, of purpose. Fruit here is not just organic matter—it is metaphysical ephemera.

The soul bruises. The soul rots. And Goya, unflinching, paints both with the same pigment.

Goya’s Palette of Illness

What shade is sorrow? What hue does despair stain the world with? Goya answers through decomposed oranges, sickly greens, bile-colored shadows. His palette rejects beauty for truth.

Even light in his works feels ill. It does not illuminate—it exposes.

Wormholes Through Innocence

A peach, perhaps, once plump and innocent, now punctured. These wormholes, sometimes subtly hinted, speak of unseen violences—small but fatal. They evoke time not as chronology but as corruption.

Innocence isn’t lost; it’s eaten from the inside.

The Gravity of Texture

Goya paints with a thickness that verges on tactile. The fruit isn’t just seen—it’s felt. One can almost touch the yielding skin, the sour pulp, the sticky decay.

Texture becomes testimony. Smoothness is a lie, and Goya tells the truth with bumps, bruises, crusted sap.

Still Life as Silent Scream

His still lifes do not scream audibly. But silence, here, is louder than agony. The fruits do not move, yet the eye trembles before them. Their arrangement, fixed yet unsettled, traps us in quiet panic.

They are not portraits of death—they are echoes of living too long.

Time’s Fingerprints on Flesh

Each wrinkle on fruit skin is time’s fingerprint. Each mold speck a signature of forgotten days. Goya transforms fruit into calendars of demise.

Unlike traditional vanitas, which moralize decay, Goya’s approach is more intimate—almost compassionate. He does not preach. He grieves.

Between Baroque and Blackness

Though Goya lived after the Baroque, he inherits its drama—then infects it with existential infection. His lighting still recalls Caravaggio, but the message is lonelier.

There is no divine here. Only deterioration. If there’s a god in these paintings, it is silent, and perhaps asleep.

Death in the Light of Day

Unlike some still lifes cloaked in night, Goya’s are often exposed to ambiguous daylight. This cruel light does not heal—it reveals the wounds more clearly.

Death is not hiding. It is seated at the table.

Fragments of Forgotten Feasts

We are late to the table. The meal has rotted. Goya invites us not to dine, but to reflect on what we’ve missed—or discarded.

Crumbs, peels, half-eaten offerings—all relics of appetite. But here, appetite turns to nausea.

Quiet Violence in Brushstrokes

There’s no overt chaos, no slashing storms. Yet violence lives in the way the paint drips, in the curve of the blade, in the rot’s slow conquest. Goya’s violence is patient.

It doesn’t erupt. It seeps.

A Psychologist with a Palette

To see Goya’s still life is to be psychoanalyzed without words. Each fruit is a test. Each bruise a confession. Each shadow a suppressed scream.

He was not only a painter, but an excavator of buried fears. A Freudian before Freud.

Aftertaste: Rotting Memory and Lingering Color

Long after the painting fades from view, it lingers. Not as an image, but as an odor, a taste, a vague unease. Goya’s gift is to haunt.

Color remains—deep, sick, unforgettable. Even decay has its palette.

FAQ

Who was Francisco Goya? Goya was a Spanish painter and printmaker, often regarded as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the moderns. His work evolved from court portraits to deeply personal and haunting images reflecting human suffering.

Why did Goya paint rotting fruit? While not his most famous subject, Goya’s forays into still life often explored decay, mortality, and disillusionment. These works served as metaphors for personal and collective despair, especially later in life.

How does Goya differ from traditional still life artists? Rather than celebrating abundance or technical precision, Goya used still life as a space of psychological inquiry and existential reflection.

What is the historical context of these works? Many of Goya’s darker still lifes were created during a period of personal illness, political turmoil, and war in Spain, which deeply affected his worldview.

How does Goya use light and shadow? He employs chiaroscuro to heighten the emotional weight of decay, using shadow not just as contrast but as presence—a co-participant in the painting.

Goya’s still life is not about fruit, not really. It’s about the things we forget to mourn. About how sweetness spoils. About how time waits for nothing—not even color.

The rotting fig is your joy gone too long untouched. The bruised apple is the love you couldn’t preserve. The shadows are all the things you didn’t say in time.

In the theater of Goya’s table, hope curdles. But in witnessing that curdling, we are forced to ask: What, if anything, can we save?

That is the true bite—the one that never digests.