The Shadows of the Peach on Manet’s Tabletops

Édouard Manet

A Fruit that Carries the Weight of Light

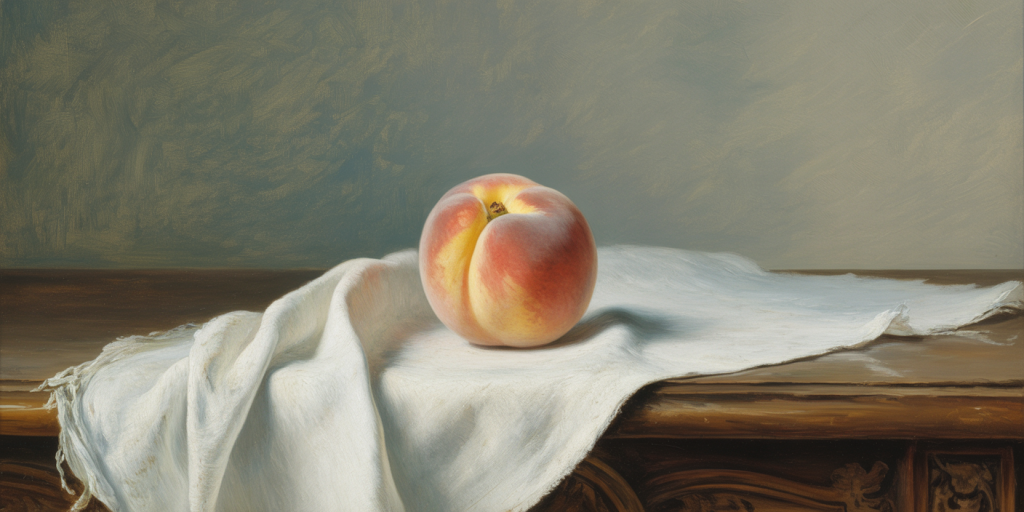

There is something profoundly still and almost trembling in the way Édouard Manet painted a peach. Resting upon a simple white cloth or a darkened wooden table, it seems to inhale gently, its skin radiant with softness and suggestion. The peach, under his brush, is not merely fruit—it is a whisper of the body, a memory of lips, a sun-soaked silence that settles into shadow.

Manet never needed grandeur to provoke. A single peach, shadowed just so, becomes an echo of an afternoon, a breath held between strangers, or the last quiet note of a conversation drifting across an open window. His tabletops are not arrangements—they are encounters. And on them, the peach casts not just a shadow, but a soul.

Table of Contents

- The Flesh Beneath the Light

- Shadows that Murmur on Linen

- The Weight of a Peach on Time

- The Knife that Waits Beside Desir

- A Table as a Theatre of Emotion

- The Solitude of Fruit

- Color Like a Withheld Breath

- Manet’s Gaze and the Female Peach

- The Echo of the Absent Hand

- Chiaroscuro of the Intimate

- Sensuality in Restraint

- A Slice That Never Cuts

- The Interior Space of Ripeness

- Light as a Lover

- The Peach as a Self Portrait

- When Composition Becomes Confession

- The Final Pause Before Decay

The Flesh Beneath the Light

In Manet’s peaches, light does not simply fall—it caresses. It follows the swell of the form like fingertips following breath. The peach’s skin glows from within, as if it remembered sunlight and was reluctant to forget.

This light reveals more than texture. It exposes vulnerability, the quiet exposure of something tender and alive. Symbolically, it becomes the light of consciousness—unfolding slowly, without violence.

Shadows that Murmur on Linen

The shadow of a peach in Manet’s world is never heavy. It hovers, diffused, like the trailing edge of a sigh. On linen, it forms a halo more than an absence—reminding us that even in stillness, nothing is without consequence.

Technically, his shadows balance weight and softness. They ground the fruit but never imprison it. Emotionally, they suggest intimacy. They are the breath of a nearby body, the curl of time around the object.

Velvet Skin, Velvet Silence

There is a quietness to the peach’s surface. The way the brush moves across it feels like the whisper of cloth, or the closing of a door. The texture becomes sensation—the viewer doesn’t see it; they feel it on their tongue.

This velvetiness, both visual and psychological, is sensual without spectacle. It provokes longing, not appetite. It is less about fruit than about the idea of touch—of things not yet touched, but imagined.

The Weight of a Peach on Time

A single fruit has weight—not only physical, but temporal. It is the sum of its growth, its season, its harvest. In Manet’s hands, the peach becomes an emblem of time passed and ripeness achieved.

Symbolically, it holds the moment just before change. It is ready, but untouched. A metaphor for emotional thresholds—for the moment we hesitate, just before something sweet is lost or bitten.

The Knife that Waits Beside Desir

Often, a knife lies close to the peach. Cold, metallic, linear—opposed to the roundness, the softness of the fruit. It is a silent presence, a boundary between thought and action.

But the knife never cuts. It waits. And in that waiting, it amplifies tension. It speaks of decisions not taken, desires restrained. In Manet’s language, a knife is not for slicing, but for measuring closeness.

A Table as a Theatre of Emotion

Manet’s tables are stages—narrow, precise, exposed. Each object is an actor, each shadow a monologue. Nothing is excessive, yet everything matters.

The table is not a setting, but a psychological space. It holds what is left unsaid. The peach is not centered out of convenience—it is placed with the logic of dreams. Manet composes emotion, not objects.

Stillness as Seduction

His still lifes do not scream for attention. They lure. Through softness, through restraint, through the disciplined caress of light on flesh. They seduce by inviting contemplation, not command.

This stillness is active. It draws the eye back again and again—not because it changes, but because it refuses to reveal all at once. Stillness becomes a kind of slow, continuous invitation.

The Solitude of Fruit

There is something solitary in Manet’s peaches. Even when joined by another object, they feel alone. Not abandoned, but separate—like a thought one cannot share.

This solitude is rich with implication. The fruit becomes a metaphor for selfhood, for inner ripeness. It sits not for the viewer, but for itself, bearing the fullness of its own quiet journey.

Color Like a Withheld Breath

Manet’s use of color is subtle but potent. The peach’s blush emerges not as pigment, but as suggestion. Hints of rose, amber, and gold swirl beneath the surface, barely visible, like a withheld breath.

This restraint evokes depth. Instead of shouting, the color waits to be discovered. Emotionally, it mirrors the inner life—never declared, always felt.

Manet’s Gaze and the Female Peach

There is a curious relationship between the peach and femininity in Manet’s still lifes. Round, tender, luminous—it becomes a stand-in for the female form, but without objectification.

Unlike the nudes of his era, the peach is never possessed. It retains autonomy. Manet’s gaze here is not dominion—it is reverence. The peach is not for taking—it is for witnessing.

The Echo of the Absent Hand

Nothing in the painting has just appeared. Everything has been placed. And so, the absence of the hand that arranged the peach is as powerful as the peach itself.

This invisible presence lingers. It suggests a backstory, a rhythm behind the quiet. The echo of gesture remains in the fold of cloth, in the tilt of the fruit. Presence, felt through absence.

Chiaroscuro of the Intimate

Light and shadow in Manet’s still lifes do not dramatize—they reveal. They create a chiaroscuro not of grandeur, but of closeness. Shadows are not dark—they are quiet.

The peach half in shadow becomes psychological. It is a metaphor for privacy, for duality, for what is kept within. The light does not invade—it uncovers gently, like trust.

Sensuality in Restraint

There is sensuality in every brushstroke, but it never becomes indulgent. Manet holds back, and in doing so, he allows the viewer to move forward. The peach is not lush—it is suggestive.

This restraint creates tension. It elevates the still life from depiction to meditation. The sensual becomes sacred, not in denial, but in discipline.

A Slice That Never Cuts

Even when a peach is opened in his paintings, it never bleeds. The flesh is exposed with dignity, with silence. There is no violence in the reveal.

This approach reflects a philosophy of gentleness. To show something without wounding it. The slice becomes a metaphor for emotional vulnerability—opened, but not harmed.

The Interior Space of Ripeness

More than exterior texture, Manet is fascinated by what lies within. The peach’s interior is soft, golden, radiant—not just in pigment, but in mood.

Ripeness becomes a psychological space. To be ripe is not merely to be ready—it is to be whole, complex, waiting to be shared or lost. The fruit mirrors the human condition.

Fruit and the Memory of Summer

His peaches carry the heat of summer, even when painted in winter light. They are seasonal, temporal, intimate. They bring the scent of sunlit kitchens, of markets and bare hands.

This memory is not nostalgic—it is sensory. The peach remembers warmth, and in that remembrance, brings warmth into the room. It is a vessel of time held still.

Light as a Lover

Light in Manet’s painting does not simply reveal. It touches. It curves around form, lingers on texture, highlights the peach’s cheek as if in adoration.

This light is not divine—it is human. It behaves like a lover: sometimes hesitant, sometimes bold, always drawn to the contours of desire. The peach is not illuminated—it is loved.

The Peach as a Self-Portrait

Strangely, the peach can be read as a self-portrait. It is exposed, silent, watched. It offers itself not as spectacle, but as essence. It is not what it does—it is what it is.

Manet, too, was often misread—criticized, questioned. The peach becomes his stand-in: quiet, whole, defiant in its softness. Not a symbol of excess, but of integrity.

When Composition Becomes Confession

The arrangement of fruit, cloth, table is never arbitrary. It is psychological architecture. Each object holds its place like a memory in the mind.

The painting becomes a confession—not of narrative, but of attention. Manet does not tell us what happened. He tells us how it felt to witness it. The composition is the emotion, shaped into stillness.

The Final Pause Before Decay

The peach, in its ripest moment, holds the promise of loss. It cannot last. Its beauty is the beauty of vulnerability, of time’s gentle pressure on the skin.

Manet captures it just before. Before the bruise, before the wrinkle, before sweetness slips into fermentation. It is a final pause—a moment caught not for eternity, but for truth.

FAQ – Understanding Manet and the Peach Still Lifes

Who was Édouard Manet?

Manet (1832–1883) was a French modernist painter whose work bridged Realism and Impressionism. He is known for challenging academic conventions and redefining modern art.

Why focus on a peach in his still lifes?

The peach, for Manet, symbolized sensuality, transience, and restraint. It allowed for emotional exploration through simplicity and offered rich textural and symbolic depth.

What characterizes Manet’s still lifes technically?

His still lifes are marked by subtle brushwork, delicate light modulation, restrained color palettes, and a focus on surface and atmosphere rather than elaborate symbolism.

How does Manet differ from other still life painters?

Unlike Dutch still life masters who emphasized abundance, Manet minimized. His work is quieter, more psychological. He focused on intimacy rather than grandeur.

Where can these still lifes be seen?

His still lifes—including peach studies—can be found in collections like the Musée d’Orsay (Paris), the Getty Museum (Los Angeles), and the National Gallery (London).

Final Reflections – The Fruit that Teaches Stillness

In Manet’s peaches, we do not find spectacle. We find presence. The kind of presence that holds your gaze and makes you wonder why something so small can feel so large.

He teaches us that the ordinary, when truly seen, becomes extraordinary. That the softest textures can evoke the loudest truths. That a fruit, when rendered with care, can contain the whole of human longing.

The peach does not speak. But it listens. It rests in light, it casts a shadow, and in doing so, it holds a world. Manet’s table is not crowded—but it is full. Full of what was, what could have been, and what remains.