Klimt and the Golden Serpents of Forgotten Myth

In the golden hush between dreams and the breathless dark of memory, Gustav Klimt painted serpents that slithered not through Eden, but through desire itself. His brush carved paths of gilded flame across the skin of muses, drawing forgotten myths out of the abyss and into the shimmer of eternal ornament.

It is not the myth you remember. It is the one your blood remembers. Beneath his gold leaf and lacquered skin, Klimt whispered tales from before language, where the divine was feminine, coiled, and knowing. His serpents do not bite; they seduce. They do not hiss; they hum, ancient and slow, across velvet-fleshed goddesses whose silence speaks of altars long crumbled.

Table of Contents

- The Gilded Dream Awakens

- Embers Beneath Ornament

- Skin Like Burnished Relics

- The Spiral of the Sacred Serpent

- Eyes of Forgotten Oracles

- Gold as a Language of Desire

- The Mute Choral of Eros

- Temples Draped in Pattern

- Where Shadows Tremble in Lustre

- The Halo of Flesh and Flame

- Secrets Encased in Mosaic

- Sensuality as Prophecy

- Scent of Lost Goddesses

- Between Symbol and Spell

- The Myth That Was Never Written

- Veins of Lapis, Breath of Fire

- Whispering Between Silks

- Daughters of Ophidian Memory

- Klimt’s Altar to the Unnamed

- Final Glimmers in the Labyrinth

The Gilded Dream Awakens

Klimt does not begin with form. He begins with reverie. The canvas is not prepared—it is enchanted. His gold is not decoration, but divination, alchemizing the flat into the eternal.

As his serpents rise from the ether, they bring with them the first breath of myth. They coil not on the earth but in the aether, suspended like incense smoke in a sacred chamber. A goddess does not pose; she emerges, faceless yet familiar, her body a scripture of curves and shimmer.

Embers Beneath Ornament

Behind the intricate filigree lies a fever. Klimt’s works pulse with the heartbeat of buried flame. Every curl of pattern is a veil stretched over longing. The fire is not extinguished—it is gilded.

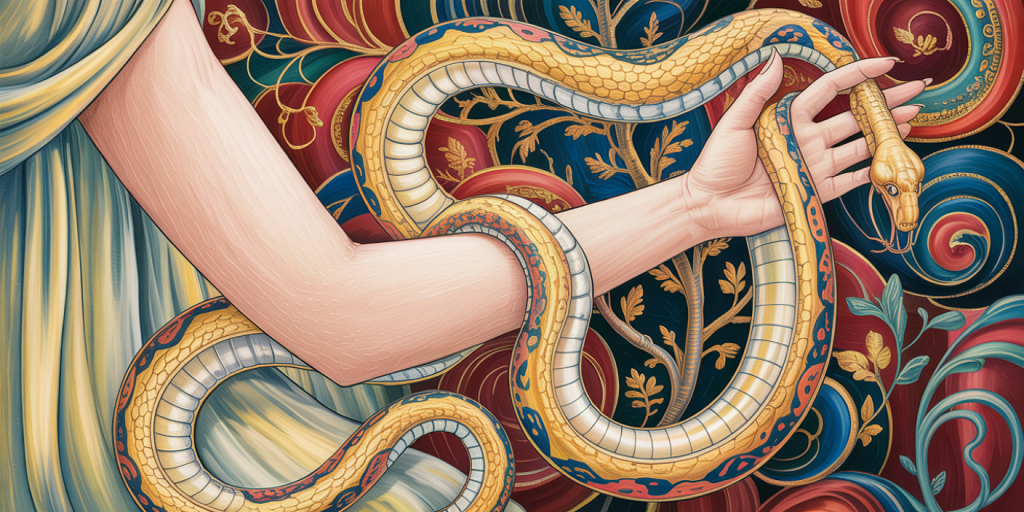

We do not see flames, but we feel the warmth. The serpents are guardians of that heat, gliding along torsos and thighs with reverent hunger. Their scales reflect the light of centuries-old rituals.

Skin Like Burnished Relics

His women are not painted; they are unearthed. Skin is rendered as relic, smooth and glowing as if polished by centuries of adoration. Each shoulder and hip is an artifact, a shrine to mortal divinity.

The sensation is tactile, sacred. You do not look at Klimt’s women—you approach them, like stepping barefoot on marble soaked in the afternoon sun of forgotten temples.

The Spiral of the Sacred Serpent

Serpents in Klimt are not symbols of sin. They are the spiral of sacred knowledge. Their curves mimic the motion of galaxies, the architecture of DNA, the flow of breath in a sleeping chest.

Coiling around female forms, they bind and liberate. They are both the boundary and the invitation, protectors of erotic mysteries encoded in gold.

Eyes of Forgotten Oracles

Klimt’s faces are rarely conventional. Some are masked in abstraction; others gaze with the silence of ancient stone statues. But their eyes, when open, are oceans of drowned prophecy.

Each glance pierces beyond the visible. It does not seduce; it summons. Through these eyes, forgotten oracles speak, reminding us that beauty was once a divine curse.

Gold as a Language of Desire

Gold is not merely Klimt’s medium. It is his vocabulary. With it, he speaks of bodies without touching them, of hunger without devouring. Gold drips where sweat would fall, glistens where breath would pause.

In Klimt, gold becomes flesh, and flesh becomes relic. It binds desire in the sacred. Through this gilded tongue, he inscribes the pulse of unspoken lust into history.

The Mute Choral of Eros

There is music in his silence. No mouths open in Klimt’s world, and yet a choral rises: of moans unsung, prayers unspoken, vows whispered against trembling collarbones.

This is the music of Eros, not in climax, but in coil—the breath before the kiss, the shiver beneath the gaze. Klimt paints the ache, not the answer.

Temples Draped in Pattern

Each composition is a cathedral of design. Backgrounds dissolve into tapestries, not as mere ornament, but as cosmic cartographies. His patterns are not flat—they vibrate with energy, as if each symbol holds a secret name.

The women are both worshipped and woven into the temple. Their limbs vanish into swirls and symbols, as if being absorbed by sacred geometry. They are not lost. They are home.

Where Shadows Tremble in Lustre

Klimt’s shadows are subtle but alive. They tremble beneath gold like a breath held too long. There is always a tension: light that yearns to darken, shadow that longs to gleam.

In this tension lives the myth itself—half forgotten, half remembered. Klimt paints the moment where shadow kisses skin, and the past flickers awake.

The Halo of Flesh and Flame

The flesh is not separate from the flame. In Klimt’s women, body and aura are one. A thigh gleams not just with light, but with heat. Their presence is elemental.

They burn without consuming. Their halos are not saintly—they are erotic coronas. The myth reborn here is not of purity, but of power.

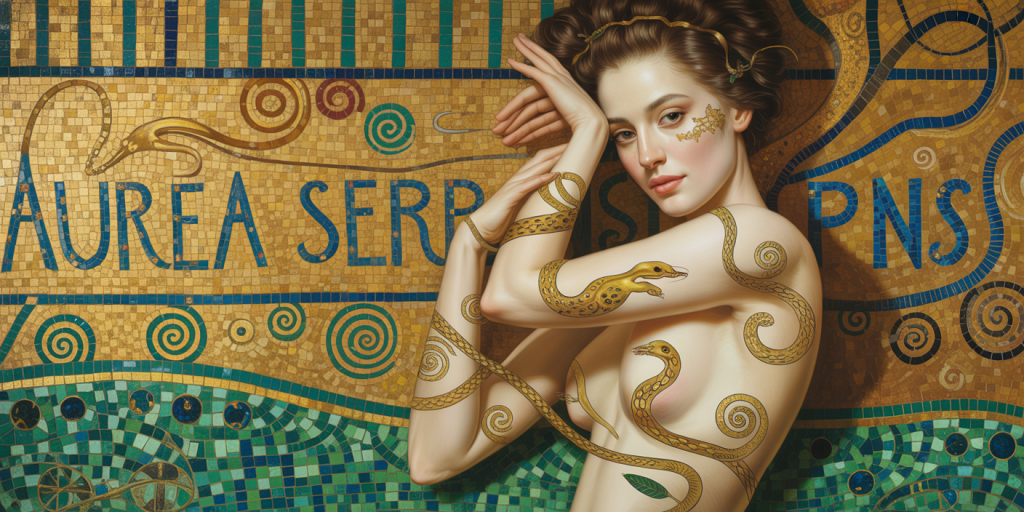

Secrets Encased in Mosaic

Each tiny square, each shard of color, is a fragment of some broken divine mirror. His mosaic technique does not just decorate—it fractures and reassembles. The image becomes myth through multiplication.

In every detail, a secret is held. In every pattern, a whisper. Klimt’s serpents are not alone in their symbolism; they share space with eyes, flowers, triangles—sigils of meaning waiting to be read by the willing.

Sensuality as Prophecy

To Klimt, sensuality is more than pleasure. It is vision. His women do not merely invite; they foresee. Their nakedness is not vulnerable but visionary. They expose the future through the prism of flesh.

It is prophecy through posture. The curve of a back becomes a horizon. A navel becomes a well. A closed eye becomes an eclipse of revelation.

Scent of Lost Goddesses

Though his art is visual, it stirs olfactory memory. One can almost smell the incense, the musk of warm skin against silk, the scent of pages bound in gold-leaf prayer.

His serpents coil in perfume. The myth he conjures has no words, but it has fragrance: ancient, earthy, and endlessly feminine.

Between Symbol and Spell

Klimt’s symbolism is not fixed—it is fluid. A spiral may mean seduction today, rebirth tomorrow. His iconography is spell-like, meant to be felt, not explained.

The viewer is not a spectator, but an initiate. To look upon his work is to be gently ensorcelled, drawn into the ouroboros of meaning.

The Myth That Was Never Written

Klimt’s myth is not found in Homer or Ovid. It exists outside narrative. His goddesses are not named, because they never needed names. They existed before stories were told.

He invents a myth through gesture and gold. A myth that lives not in temples or texts, but in the curve of a hip, the gleam of an eye. A myth that once whispered, still echoes.

Veins of Lapis, Breath of Fire

Blue and red appear like veins in his compositions—rare but potent. The blue is lapis lazuli, sacred and ancient. The red is fire, menstrual or divine. Each line pulses.

They carry blood through the gold. Life through the dream. Klimt’s palette is a circulatory system of myth and memory.

Whispering Between Silks

Textile plays a quiet yet vital role. Drapery caresses the women, neither concealing nor revealing, but amplifying. The silk is another voice—a murmur of status, of seduction, of ceremony.

The patterns do not separate the woman from the world. They bind her to it. Klimt’s fabrics whisper lullabies to the lost divinities.

Daughters of Ophidian Memory

His women are serpentine in posture and presence. Not malicious, but mysterious. Their very curves recall the first movements of life in primordial waters.

They are Eve before shame. Medusa before vilification. Lilith before exile. They are the daughters of an ophidian memory Europe tried to forget but Klimt painted in pure gold.

Klimt’s Altar to the Unnamed

In his art, there are no saints. Only priestesses of presence. Klimt builds an altar not to religion, but to rapture, not to salvation, but to sensation.

He names nothing, because naming tames. Instead, he illuminates. His altar glows with silence and surrender. Here, the unnamed are finally crowned.

Final Glimmers in the Labyrinth

To exit a Klimt is to leave a labyrinth of gold, longing, and forgotten reverence. One emerges altered, bathed in the shimmer of secrets and shadows.

His golden serpents still move when the eyes close. They slither through memory, myth, and dream, leaving behind the echo of divinity not as doctrine, but as desire.

FAQ

Who was Gustav Klimt?

An Austrian Symbolist painter, Klimt was one of the most prominent members of the Vienna Secession movement. He is known for his erotic, mystical, and gold-embellished portraits, often celebrating the feminine as divine.

What does the serpent symbolize in Klimt’s work?

Rather than biblical sin, the serpent in Klimt symbolizes knowledge, sensuality, feminine power, and the cyclical nature of life and myth.

Why is gold so central in Klimt’s paintings?

Klimt used gold not merely for beauty but to evoke timelessness, sacredness, and transformation. It creates a ritual space on the canvas.

What is the meaning behind the patterns and mosaics?

They reference Byzantine art, ancient temples, and esoteric symbolism. They dissolve the boundary between the figure and the infinite.

How does Klimt’s work relate to mythology?

Rather than illustrating specific myths, Klimt evokes archetypal, often feminine myths that feel ancient and unnamed. His work is mythopoetic rather than narrative.

Final Reflections: The Gold that Remembers

Klimt’s golden serpents are not decoration—they are remembrance. They recall the divinities cast out by reason, the goddesses buried beneath stone churches, the sensual wisdom repressed by history.

In each line, each shimmer, he reclaims a myth not from the past, but from the body. He teaches us to see not just with eyes, but with longing. Not to name, but to feel.

And in that feeling, the myth lives again.