The Science of Motivation: What Really Drives Us

Motivation is the invisible engine powering human behavior, shaping our desires, decisions, and ultimately our achievements. From the moment we wake up to the choices we make throughout the day, motivation plays a crucial role in defining our personal and professional lives. Over decades, psychologists, neuroscientists, and behavioral economists have investigated the mechanisms behind motivation to understand what truly propels individuals toward their goals. Grasping these underlying principles not only ensures greater self-awareness but also offers practical strategies to optimize productivity and well-being.

In this article, we explore the science behind motivation, examining the psychological frameworks, biological factors, and social influences that drive human actions. Real-world examples and data-backed insights will illuminate key concepts, while comparative analyses guide readers on how different motivational theories apply in various contexts. Lastly, we forecast emerging trends and potential breakthroughs that promise to deepen our comprehension of what fuels motivation in the future.

Understanding Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

One of the foundational distinctions in motivation science is between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to engaging in an activity for its inherent satisfaction rather than for some separable outcome. A classic example is a child playing a musical instrument simply because they find joy in the music. Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, involves performing a task to earn a reward or avoid punishment, such as an employee working overtime for a bonus.

Research by Ryan and Deci (2000) on Self-Determination Theory (SDT) highlights that intrinsic motivation leads to higher-quality learning and sustained engagement, largely because activities align with personal values and interests. Intrinsic motivators are more autonomous, fostering creativity and resilience. Conversely, extrinsic motivation can be effective for short-term goals, especially in structured environments like workplaces. However, over-reliance on external rewards can diminish intrinsic interest, a phenomenon known as the “overjustification effect.”

A practical case is Google’s “20% time” policy, which encourages employees to spend one day a week on projects of their choosing. This initiative taps into intrinsic motivation, fueling innovation and job satisfaction beyond mere salary increments. Conversely, traditional corporate environments heavily emphasizing bonuses often see motivation fluctuate with financial incentives but may sacrifice long-term engagement.

| Aspect | Intrinsic Motivation | Extrinsic Motivation |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Internal satisfaction | External rewards or punishments |

| Duration of Effect | Long-term engagement | Often short-term or conditional |

| Examples | Learning for fun, creating art | Working for bonuses, studying to avoid failing |

| Impact on Creativity | Enhances creativity and innovation | May limit creativity by focusing on outcomes |

| Risk | Possible boredom if interest fades | Risk of dependency on rewards |

The Neuroscience Behind Motivation

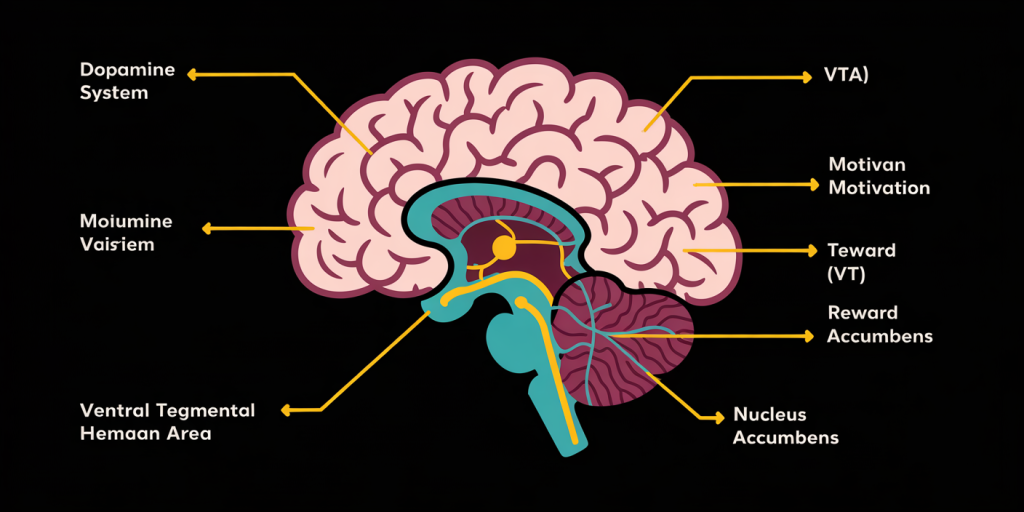

Beyond psychological theories, motivation is deeply rooted in brain function. Neuroscience reveals that several brain regions and neurochemical pathways contribute to motivated behavior. Central to this is the dopamine system, part of the brain’s reward circuitry. Dopamine release signals the anticipation or receipt of rewards, reinforcing actions and enhancing motivation.

Studies using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) show increased activity in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens during reward processing. These areas are linked to pleasure and reinforcement learning. Notably, dopamine not only responds to rewards but also to cues that predict rewards, explaining why motivation can be spurred by anticipation.

Real-life examples include addiction, where the brain’s reward system is hijacked, leading to compulsive behavior due to overactivation of dopamine pathways. Conversely, motivation deficits observed in disorders like depression or Parkinson’s disease are associated with diminished dopamine function, resulting in apathy and decreased goal-directed activity.

Furthermore, research into brain plasticity shows that motivation can influence neural adaptations. For instance, motivated learning triggers stronger synaptic connections, reinforcing memory consolidation. This explains why motivated students typically perform better and retain information longer.

Psychological Theories Explaining Motivation

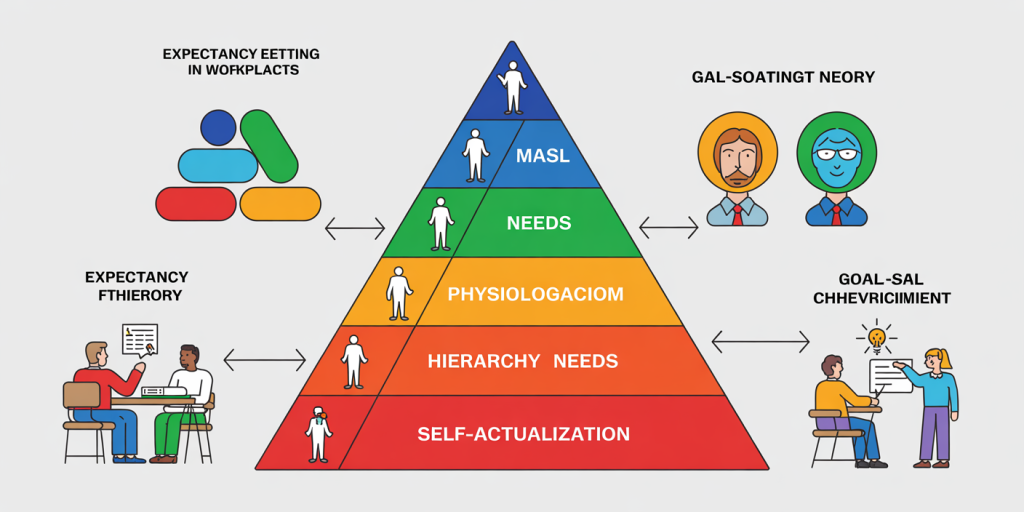

Different frameworks have been proposed to explain motivation from psychological perspectives. Among the most influential are Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Expectancy Theory, and Goal-Setting Theory, each emphasizing unique facets of motivation.

Maslow’s model (1943) presents a pyramid of human needs, beginning with physiological necessities progressing to self-actualization. According to Maslow, individuals must satisfy lower-level needs like food and safety before pursuing higher levels like esteem and purpose. This hierarchical approach helps explain how workers struggling with job security might remain unmotivated by leadership praise or opportunities for personal growth alone.

Expectancy Theory, developed by Victor Vroom (1964), posits motivation depends on the expected outcome of an action. If the perceived effort will lead to a desirable reward, motivation increases. This theory emphasizes rational decision-making, making it applicable in organizational settings where employees weigh inputs versus outcomes.

Goal-Setting Theory by Locke and Latham (1990) asserts that specific, challenging goals result in better performance than vague or easy goals. Clarity and feedback are essential components, encouraging individuals to monitor progress and adjust efforts. NASA’s Apollo program offers a prime example: the explicit mission to land a man on the moon drove the entire organization’s focus and innovation.

The following table compares these theories briefly:

| Theory | Key Concept | Application Example | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maslow’s Hierarchy | Need prioritization | Employee well-being programs | Holistic view of human needs | Less predictive, hard to test |

| Expectancy Theory | Outcome expectancy | Performance-based bonuses | Applicability to rational decisions | Ignores emotions |

| Goal-Setting Theory | Specific, challenging goals | Space missions, sales targets | Clear guidance and feedback | May cause excessive pressure |

Social and Environmental Influences on Motivation

Motivation does not operate in a vacuum; social context and environment heavily influence it. Social motivation theories emphasize human need for affiliation, recognition, and belonging. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory stresses the role of observational learning and self-efficacy—the belief in one’s capability to execute actions.

Workplaces exemplify this: employees motivated by supportive management, peer recognition, and positive culture often demonstrate higher retention and performance. Google’s employee-friendly amenities and open communication policies contribute to a motivating environment that nurtures creativity.

Environmental factors such as physical workspace, noise levels, and access to resources also impact motivation. Bright, well-ventilated offices are linked with increased productivity, while cluttered or stressful environments reduce motivation. In education, classrooms designed to stimulate curiosity—through interactive tools and nurturing teacher-student relationships—enhance student engagement.

A study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology (2019) found that employees who felt socially connected at work were 45% more motivated and 30% more productive than those who felt isolated. This illustrates the profound influence of social dynamics on motivation.

Practical Applications: Enhancing Motivation in Everyday Life

Understanding motivation science allows practical application in diverse domains like education, workplace management, and personal development. For educators, incorporating intrinsic motivators—such as autonomy, mastery, and purpose—can foster lifelong learners. The “flipped classroom” model is one such approach, empowering students to engage actively and independently.

In corporate contexts, blending intrinsic and extrinsic incentives proves most effective. Transparent communication of goals, career development opportunities, and meaningful work increase intrinsic motivation, while appropriate bonuses and recognition address extrinsic needs. For example, the multinational company Salesforce combines performance bonuses with its “Ohana Culture,” emphasizing family bonds and community support among employees.

Personal development techniques, such as setting SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) goals, promote clarity and focus. Visualization and self-reflection exercises reinforce motivation by aligning goals with personal values. Additionally, tracking progress through journals or apps provides necessary feedback loops identified by Goal-Setting Theory.

Future Perspectives on Motivation Research

As technology evolves, the science of motivation is poised to reach new frontiers. Advances in neuroimaging and wearable sensors may allow real-time monitoring of motivational states, enabling personalized interventions to enhance productivity or mental health.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) also holds promise for motivation research. Through analyzing vast behavioral data, AI can predict motivational lapses and suggest customized solutions. Gamification, already used in education and fitness apps, will likely become more sophisticated, incorporating adaptive challenges that maintain user engagement without causing burnout.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary approaches integrating genetics, psychology, and sociology may uncover how innate predispositions and cultural factors interact to shape motivation. For instance, preliminary studies suggest gene variants affecting dopamine receptors correlate with differing motivational traits, opening personalized medicine and coaching possibilities.

Ethical considerations will be paramount as these technologies develop. Ensuring autonomy and privacy while harnessing motivational science will require ongoing dialogue among scientists, policymakers, and society.

—

The multifaceted nature of motivation reflects the complexity of human behavior itself. By integrating psychological theories, neuroscientific evidence, and social dynamics, we gain a comprehensive understanding of what drives us. This knowledge empowers individuals and organizations to craft environments and strategies that nurture motivation, leading to healthier, more fulfilling lives. With future innovations on the horizon, our grasp of motivation’s intricate science is likely to deepen even further, unlocking potentials once thought unreachable.