William Blake and the Fiery Vision of the Solitary Creator

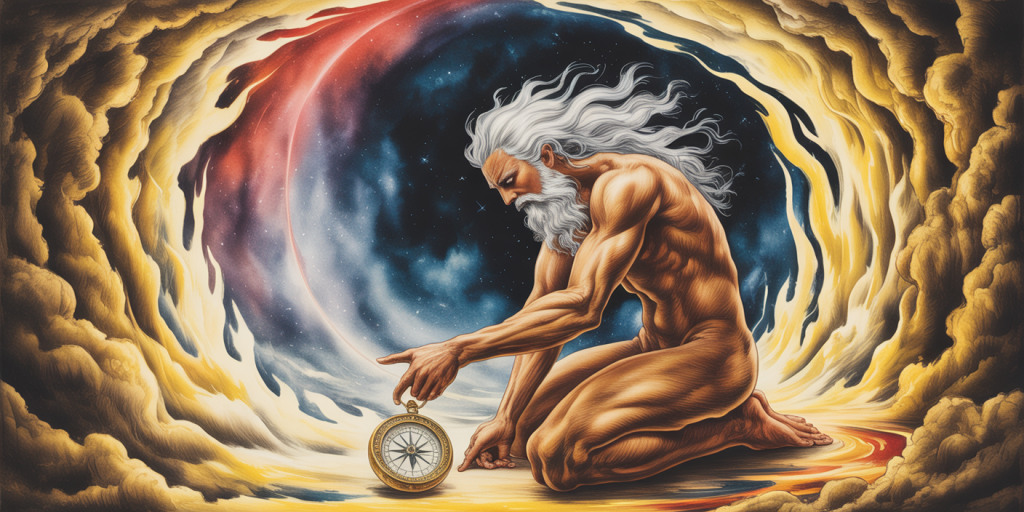

In the molten crucible of vision and flame, William Blake stood alone, bearing witness to a world cleaved open by divine fire. His art does not illustrate—it prophesies. Within the trembling parchment of his works, we see not merely figures and lines, but the trembling blueprint of creation itself, caught mid-thought, mid-breath, mid-apocalypse.

Blake did not paint the world as it is. He painted the world as it burns behind the veil of perception, as it trembles with sacred intention. In his solitary Creator, cast in fire and compass, we see both judgment and genesis, the hand that builds and the hand that binds. His is a universe that glows not with sunlight, but with inner flame—the light of revelation, rage, and radical imagination.

Table of Contents

- The Forge of the First Thought

- Embers Behind the Eyes

- Muscles of the Metaphysical

- The Hand That Measures the Abyss

- A Universe Drawn in Judgment

- Gold on the Edge of Damnation

- The Silence of Exploding Stars

- Anatomy of a Sacred Scream

- The Compass as Covenant

- Flesh Woven in Radiance

- The Solitude of God

- Geometry of Divine Terror

- Light Torn from the Veil

- Ashes in the Corner of Heaven

- Rage Etched in Rapture

- Fire as the Final Language

- Touching the Flame of Archetype

- The Prophet Who Painted Thunder

- Eyes Like Cataclysms

- The Last Architect

The Forge of the First Thought

The image begins not in paint, but in incantation. Blake’s Creator emerges from an alchemical storm, a figure forged of thought and thunder. He kneels, yet he dominates; he bends, yet the universe itself bows to his measurement.

The composition is elemental: spirals of flame encase the godhead, curling like solar flares around his muscled form. This is not anatomy but apocalypse. His hair flows like lava. His breath ignites the dark.

Embers Behind the Eyes

His eyes do not see—they sear. Lit from within by a fire no mortal could endure, the gaze of Blake’s Creator transcends judgment. It pierces the fabric of reality. It does not accuse; it awakens.

In this incandescent stare, we glimpse the moment just before Genesis, the pain of separation from chaos. To look into these eyes is to remember what it felt like to be an idea in the mind of God.

Muscles of the Metaphysical

Blake’s figures are sinewed with spirit. The Creator’s body is a cathedral of strain and force, each limb trembling with metaphysical tension. He does not float in serenity—he wrestles with space itself.

His arms extend like bridges between being and becoming. Shoulders bear galaxies. Fingers press into time. This is flesh sculpted from invocation, not clay.

The Hand That Measures the Abyss

The compass in the Creator’s hand is no mere tool—it is the axis of destiny. With it, he carves the perimeter of being, separating light from dark, heaven from earth, the finite from the eternal.

This gesture is not neutral. It is judgment made manifest. The arc he draws is sacred geometry, a covenant of limitation, of divine constraint upon chaos. The abyss is not conquered—it is given form.

A Universe Drawn in Judgment

Blake’s composition divides the canvas as the Creator divides the cosmos. Each line is intentional, heavy with consequence. His universe is not a playground of stars—it is a courtroom of meaning.

Everything exists within the bounds of divine decree. Even light must answer for its brightness. Color serves not emotion but law. This is a cosmology governed by fire and form.

Gold on the Edge of Damnation

Color in Blake is theological. The golds of flame do not comfort—they cauterize. His palette sears. Red is not passion, but prophecy. Black is not absence, but presence of judgment.

The Creator himself glows not with benevolence, but with necessity. His light is the edge of grace, the flare before collapse. In his hues, we see the torment of order imposed on the unformed.

The Silence of Exploding Stars

Though Blake’s art is static, it explodes in silence. His stillness is not peace, but a moment suspended in sacred violence. One can almost hear the roaring hush of stars dying into form.

This is creation by combustion. The void does not gently yield—it is burned away. And in the hush that follows, time itself begins.

Anatomy of a Sacred Scream

Every tendon in the Creator’s body screams. Not with pain, but with purpose. His strain is not suffering—it is sacrifice. The arch of his back, the spread of his limbs—they are the gesture of genesis.

Blake paints not emotion but essence. The body becomes a sigil, a scream pressed into posture. It is the geometry of divine agony.

The Compass as Covenant

The compass is both tool and symbol. It echoes the circles of Dante, the spheres of Ptolemy, the orbits of soul and judgment. In the Creator’s grip, it becomes pact: that nothing exists without measure.

It is terrifyingly gentle. The tips of the compass do not pierce; they trace. Yet this tracing binds the cosmos. It is creation as contract.

Flesh Woven in Radiance

The texture of Blake’s divine flesh is luminous. It glows like scripture read by lightning. Lines pulse with inner light, as though his skin is stitched from dawn and fury.

To touch this flesh, if one could, would be to touch meaning itself—raw, scalding, ecstatic. In his depiction, light and limb are inseparable.

The Solitude of God

This Creator is utterly alone. Not lonely, but solitary in the cosmic sense. His solitude is pre-time, pre-voice. He crouches not above creation, but at its threshold.

There is no chorus of angels, no divine audience. Just him and the darkness. His posture is that of burden: to birth the world from within oneself.

Geometry of Divine Terror

Blake’s lines are sharp, uncompromising. They do not suggest—they declare. The spiral of flame, the arc of the compass, the taut limbs: all form a geometry that induces awe and terror.

This is sacred math—formulas etched in rapture. The terror is not in violence, but in precision. In Blake, even awe has an angle.

Light Torn from the Veil

Light in Blake does not illuminate—it rends. It is not diffused, but directional, sharp, and purposeful. It slices through the void like a sword of consciousness.

His use of chiaroscuro is spiritual, not optical. Darkness is not the absence of light but its opposite. Light is divine rupture.

Ashes in the Corner of Heaven

In the corners of Blake’s compositions, faint shadows linger. These ashes of former selves, forgotten rebellions, or discarded creations murmur in smudge and blur.

Heaven, for Blake, is not sterile. It bears scars. The divine is not pristine—it is tested. Ashes remind us that even light has history.

Rage Etched in Rapture

Blake’s Creator is not coldly omnipotent. He is furious, fervent, aflame. Rage does not contradict holiness—it fulfills it. This is not wrath against man, but against formlessness.

His muscles surge with rapture. Not joy, but divine intoxication—the ecstasy of will becoming form. In this, creation is closer to birth than blueprint.

Fire as the Final Language

Language in Blake is visual, elemental. Fire speaks when words collapse. Flame is grammar. Ember is punctuation. The composition burns with syntax of revelation.

His fire writes the gospel of sight. The canvas is both scripture and spell. The reader is meant not to understand—but to ignite.

Touching the Flame of Archetype

The Creator is not a character. He is an archetype: the Architect, the Initiator, the Flamebearer. Blake reaches beyond persona into primordial form.

Touching this flame is dangerous. It burns away name, age, and ego. One is left only with essence—and awe. This is Blake’s sacred violence.

The Prophet Who Painted Thunder

Blake was not an illustrator. He was a prophet with a paintbrush. His works are not depictions but declarations. He does not show—he reveals.

To look at his Creator is to hear thunder in the soul. Not noise, but the sound of meaning arriving.

Eyes Like Cataclysms

The eyes of Blake’s divine figures are cataclysms. They are not set in the face—they erupt from it. Light pours from their pupils like unspoken commandments.

These eyes contain endings and beginnings. They are not windows to the soul—they are the soul, made flame.

The Last Architect

In a world of entropy, Blake’s Creator remains: the final architect, forever measuring, forever forming. He is not past. He is perennial.

He kneels in every act of imagination. In every moment we bring something forth from nothing, we echo his form. He is us—and beyond us.

FAQ

Who was William Blake?

William Blake (1757–1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker known for his visionary work that blended art, poetry, and mysticism. He created illuminated books and prophetic illustrations.

What is the meaning of the Creator in Blake’s art?

The Creator, often identified with Urizen in Blake’s mythology, symbolizes reason, law, and the ordering principle of the universe. He is both necessary and tragic—a divine limiter of chaos.

Why is fire so present in Blake’s imagery?

Fire in Blake represents divine inspiration, purification, and judgment. It is both destructive and creative—a vehicle of revelation.

What artistic techniques did Blake use?

Blake combined watercolor, pen and ink, and relief etching in his unique method of illuminated printing. His lines are precise, expressive, and deeply symbolic.

Is Blake’s art religious or spiritual?

Both. Blake created his own cosmology, heavily inspired by Christianity but also critical of institutional religion. His work explores divine truth through personal vision.

Final Reflections: When Flame Becomes Form

To gaze upon Blake’s solitary Creator is to stand at the edge of the known and peer into the trembling forge of becoming. It is to witness the divine not as comfort, but as confrontation—not as father, but as flame.

In his furious tenderness, in his burning solitude, Blake gives us more than myth—he gives us a mirror. The Creator does not simply draw the world; he dares us to draw ourselves anew, in fire, in vision, in awe.